Service prices as a signal for setting (i.e. falling) CNB interest rates

Comment by Jaromír Šindel, Chief Economist of the CBA: The analysis summarizes the government's regulatory steps that will further slow consumer price growth this year, probably well below 2%. What does this mean for the CBA, which seems to be starting to deflate the pigeon balloons, at least more than at the end of last year? Given its earlier communications, where inflation is headed in 2027 should be key, which will also indicate the direction of core inflation in the months ahead. And it is not just the case of still strongly rising services prices that are the focus of this analysis, the first part of the triptych ahead of the CNB's February board meeting.

The central bank is expected to keep the two-week repo rate at 3.50% on February 5. To lower it, the CBR's current paradigm (effective from summer 2022) would require a slowdown of more than one percentage point in the momentum of core prices to 3-4%. And there, even given current price expectations (see Chart 13 here) or wage dynamics in services, we are not there. This is where a slowdown in unit labour cost growth in services from the current 5-6% pace to closer to 3% would be preferable. At 1.5-2% gains in productivity, this would require wage growth of around 5%, which is still in contrast to the current average wage growth in services of over 7% (annualized and year-over-year).

If core services price growth remained around 4.5% and the CBN wanted to commit to an interest rate cut with core inflation rising at around 2.3% (instead of the current 2.8% momentum), then a slower pace of imputed rent would be required with near-zero growth in tradable core goods. Namely, around 3%, instead of its current 4.5% annualized rate.

In conclusion, we can start by noting that we are significantly better off regionally in terms of service prices, which is of course reflected in the current monetary policy rate settings in the region (the CNB at 3.5% vs. the Polish central bank at 4% and the Hungarian central bank at 6.5%).

Note: Unless otherwise stated, we work with seasonally adjusted figures in the text. Annualized developments show possible year-on-year growth if current month-on-month dynamics are maintained.

Food and government regulations were behind the slowdown in Czech consumer inflation towards the central bank's target at the end of last year and into its lower tolerance band this year. Certainly the welcome but unexpected drop in Czech consumer price growth to 2.1% at the end of last year mainly reflected lower food prices, which underperformed their usual seasonality (see fifth chart here). Instead of the realised November and December slowdown to 2.1% y/y, the November CBA Consensus Forecast expected growth of 2.7% at the end of 2025.

The same is true for the outlook for consumer inflation this year, which is likely to slow closer to 1.5% (vs. the November CBA Forecast consensus of 2.2%). This is mainly due to the transfer of the renewable energy levy from household bills (this will ease CPI growth by 0.3pp in January) to state budget spending (together with the relief for businesses, this transfer change will increase budget spending by CZK17bn to almost CZK42bn). Over the course of the year (I would guess September), this will be compounded by an increase in the student and pensioner transport discount, with a CPI impact of -0.1pp. b. And in 2027 we will most likely see another "regulatory" dent in the dynamics of Czech inflation, in the form of the abolition of licence fees for public television and radio, to the extent of about 0.3 pp.

Since the summer of 2022, when the CNB's monetary policy paradigm has changed, its main leitmotif has become the sustainability of a return to the inflation target, even in the case of core inflation (which is CPI excluding food, fuel, energy and administered prices). The rationality of this condition already reflects the experience of the "Rusnok" Bank Board, when in 2019 both headline and core inflation were dangerously close to the 3% upper limit of the tolerance band of the inflation target (both of which had been in the upper tolerance band since 2017). After all, in the current world full of geopolitical and climate shocks, relying on lower food and energy prices to sustain disinflation can be a tricky business for a central banker (and especially when we haven't done that much with so-called resilience to supply shocks).

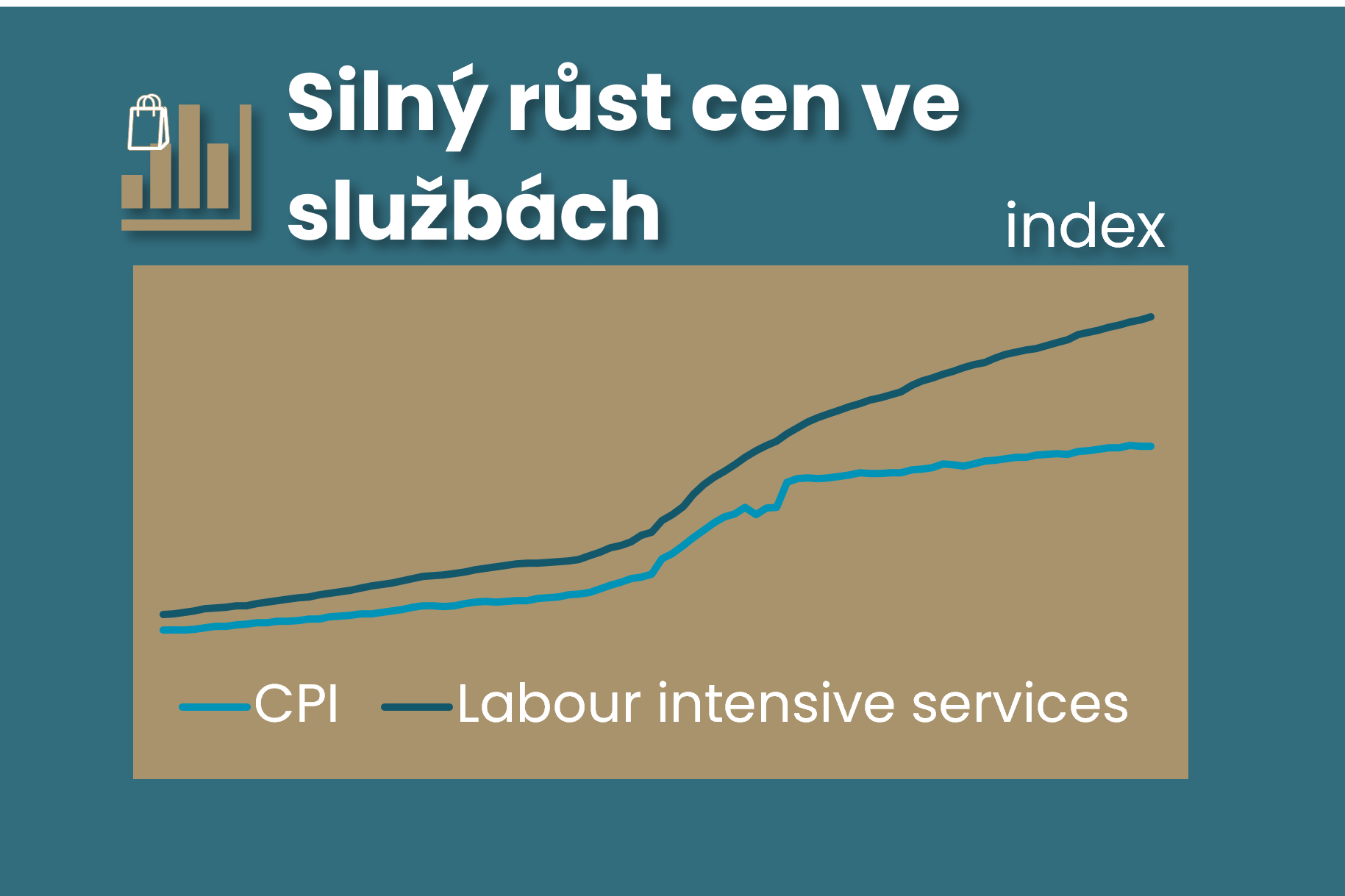

It is services that represent a structural brake on a faster slowdown in core inflation. And if we look at the current reality of Czech core consumer inflation, we see it at around 2.8% of future annual growth in the last three months of last year, well above the centre of the inflation target and still close to its tolerable upper limit. This reflects rising service prices of around 4.9% (here excluding imputed rents). And if we look at the growth rate of prices of labour-intensive services, it returned even closer to the 5% moment at the end of last year. And prices of core services (with a weight of around 40% in core inflation) are not alone in this. Their stronger growth is complemented by the aforementioned imputed rents (with a weight of just under 20%) with a 4.5% momentum at the end of last year (but more on that next time).

The impact of these strong dynamics on the less than 3% growth in complete core inflation was offset by the near-zero pace of tradable goods prices (more influenced by the exchange rate and demand, but also by Chinese supply, than by the labor or real estate markets).

The main reason why consumer, and hence core, inflation was returning to target more slowly was the persistently high price growth in services, especially in their labour-intensive segments. This development reflects deeper changes in the Czech economy. Since around 2018, the Czech economy has been moving away (not entirely successfully) from an industrial export-oriented economic model, which is a natural process for growing economies. This has been compounded by the "end of cheap labour" slogan in the pre-Cold War period, which has allowed for a demographic slump in labour market supply, as well as more significant increases in pensions. As household incomes have risen, the structure of consumption has changed - alongside goods, demand for services has grown, and this demand has grown stronger as incomes have risen.

Unlike industry, services are significantly more labour-intensive and their productivity growth is more moderate. Yet in many service industries - from personal services to transport to home care and patient care - the scope for automation is more limited. Any shortage of workers therefore translates very quickly into wage increases and, consequently, into price increases. This is precisely the mechanism that is evident in the Czech economy and is reflected in stronger growth in unit wage costs (a reflection of growth in total wage costs within GDP or growth in average wages relative to productivity). At the same time, the phenomenon of the trend towards a stronger nominal koruna, which has dampened wage growth in industry as productivity has risen, and hence the spillover of stronger wage growth across the economy, including the service sector, is absent.

The situation has been further exacerbated by the covid-19 pandemic, with a negative supply shock, especially in services, and the ongoing demographic downturn, which is only partially cushioned by foreign workers. A number of workers left the service sector temporarily or permanently during the pandemic. This mismatch has created stronger wage pressures in services, which have persisted thanks to the recovery in demand. An ageing population is increasing demand for health, social and care services, while the labour supply is becoming thinner over the long term. At the same time, public sector demand for employees in education, health, security forces and the military remains strong. These sectors compete for labour with market services, contributing to the overall increase in wage costs in the economy.

The data show that labour-intensive services - personal services, repairs and maintenance, transport, patient care and household services - are the most expensive today. These items are not only rising faster than headline inflation after the pandemic, but have also outpaced wage growth in recent years, suggesting a persistent imbalance between supply and demand.

International comparisons also show that part of the current price developments in services are converging. Before the pandemic, the price level of services in the Czech Republic was well below the euro area average, especially for individual public sector services, but also for services purchased by households. The positive news is that the rate of growth in services prices has been gradually slowing down in recent years and is now approaching the trend in the euro area or Germany in international comparison (orange line in the graphs below).